Price Anchoring: Influencing Sales with Different Price Tiers

By

|

Last updated on

When Steve Jobs announced the first iPad, he told the crowd that analysts predicted he would sell it for $999. He put $999 on a big screen and let it sit there while he spoke.

When it came time to reveal the actual price, the $999 was flattened by a falling $499. With a simple animation, everyone in the room (who would undoubtedly buy an iPad) felt like they just saved $500.

What’s interesting is that no one in the room had any idea what an iPad was worth. How could they? It was a brand new product. Yet somehow they felt like they had the opportunity to buy it for less than its value.

Imagine if Steve Jobs presented the price the other way. Let’s say he put $199 on the screen and later increased it to $499. Everyone in the room would feel like they just got screwed, even though they were never going to get the iPad for $199.

Like a lot of great marketers, Jobs used price anchoring to influence how people feel about a price. But you don’t have to be a tech giant to take advantage of this psychology trick.

What Is Price Anchoring?

Price anchoring is a strategy of pricing products and services that relies on the primacy effect (sometimes called the anchoring bias). The primacy effect is our tendency to rely heavily on the first piece of information we hear.

As customers, we perceive prices relatively. The first piece of information creates a frame of reference for all subsequent pieces of information.

This means you can use the first price your customers see to influence how they feel about subsequent prices. High initial prices direct their attention to the product or service’s positive qualities. Low initial prices direct their attention to the negatives.

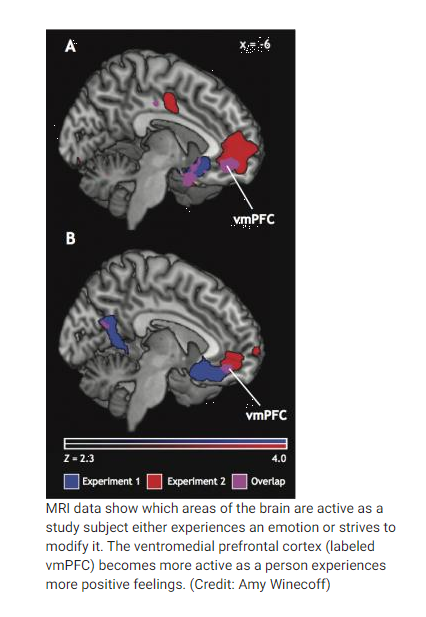

If you think that lacks logic, you’re right. That’s because logic is only part of how we evaluate purchases. Duke University discovered that we make economic decisions with the same part of our brain that determines our emotions.

The beauty of this effect is that it works even if you are aware of it. In one study, real estate agents were asked to appraise the value of a house. All of the agents presented estimates similar to the house’s list price (which the researcher’s made up) even though they denied factoring the list price into their decision. They knew the list price would influence their decision, so they tried to ignore it, but that awareness wasn’t enough to counteract the anchoring bias.

An Everyday Example of Price Anchoring

Here’s an example of price anchoring we all deal with every day.

Gasoline prices fluctuate regularly, but they generally trend upwards. They might fall a little this month based on some global event, but for the most part, they increase over time. At one point in the U.S., gas prices jumped to $4/gallon, which was quite painful.

We all cheered when gas prices started to fall. Suddenly $3.89/gallon felt like a great deal, even though the price was $2.89/gallon the year before. Why did a slight drop from an unusually high price feel like a bargain, even though we paid considerably less in the past?

We feel this way because each price we pay resets our anchor. We compare today’s price to the previous price, not the price we paid five years ago or the one time we bought super cheap gas on that road trip through the middle of nowhere. So now we look forward to paying prices we would have once thought were outrageously high.

Price Anchoring in Marketing

Gasoline is an everyday example because it’s a commodity we consume often. You probably know the prices of a few gas stations around your home or work. We have a fair understanding of its value and why its price rises or falls.

But what about less familiar products? What happens when we have to evaluate the price of a new product or service? We can’t maintain anchor points with everything like we have with gas.

We create price anchor points as soon as we start thinking about making a purchase. This means some anchor points are only seconds old by the time we make a decision. Other anchor points are weeks or months old, depending on how long it takes us to get through our buying process.

For instance, let’s say you’re looking for someone to manage your social media marketing. What’s a good price for that? It’s hard to say, especially if you’ve never purchased that kind of service. Furthermore, all social media marketing isn’t the same. It’s hard to compare one service to another.

In this case, your brain lacks a clearly established anchor, so it would create one based on the first price you see. You will subconsciously compare all subsequent prices to that first price, even if the first price was an outlier.

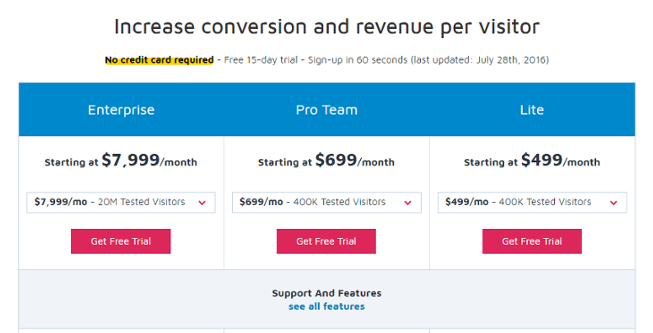

Marketers often do this by offering multiple variations of the same product at different price points. The first one you see engages the primacy bias and affects whatever you see after.

Let’s say a social media marketer offers to create 30 posts per month for $500. Or she’ll create 25 posts per month for $400. You don’t think those last five posts are worth the extra $150, so you choose the smaller option. But that’s what the seller wanted. She wanted the $400 to seem like a bargain in comparison to the $500 service.

Price Anchoring in Practice

In order to implement price anchoring, you just need to show more than one price. The first price will influence the second price. So you have two options:

- Make the first price high to create a perception of high value. Then make the second price low so the customer thinks they get high value for a bargain.

- Make the first price low to create the perception that the customer is getting a deal. Then make the second price higher so the customer associates the bargain with the products you want them to buy.

The first method is obviously more common. Marketers want their customers to think that their products and services are as valuable as possible. High perceived value + reasonable price = customers rush to buy.

The second application is less common, but it’s useful when customers are especially price-adverse. An example of this kind of price anchoring is when stores show prices of products without the tax calculated.

If you don’t have multiple prices and aren’t willing to create variations of your products, think about other price values you can display on your website. You could compare your service to your competitors or to other kinds of solutions. Or you could show costs your customers would incur if they wait too long to purchase a solution.

Going Forward

Price anchoring won’t triple your sales, but it has the power to nudge the needle a bit to boost your conversion rate. Customers will feel more comfortable about making a purchase if they think they’re getting a deal. Combine price anchoring with other marketing techniques based on psychology, like urgency, scarcity, and reciprocity for exponential results.